Games used to be simple. Score a certain number of points, use a variety of tricks to get those points, and all of your natural ability can shine through. This is still how sports works, and most board games can be boiled down to a few pieces, a few rules, and a wonderful social experience with your friends.

Video Games are a bit different. Computers have grown so powerful that they can hold a myriad of information that people would have a huge problem with. They're wonderful tools that can do things that we are really bad at, like storing the entire calculated length of pi. If you can put a number to an idea, a computer can store - and copy - the idea billions of times.

Most video games are still stuck on the same ideas that any analogue game would handle. We can do better than that... and by we, I mean myself and the computer working in concert. Let's make a human in a fantastic setting from the ground up.

A couple terms we'll need before moving forward:

Human: A digital approximation of the real world experience that our fleshy meatsuits are having.

- Most video games do this so badly that we can replace every human with a stick.

Invariant: A function, quantity, or property which remains unchanged when a specified transformation is applied.

- On a design level, this is a fundamental statement that is always the same. Sometimes it's arbitrary, more often it's because we need a foundational idea and/or restriction to build on.

With that out of the way, here's a human.

This guy has all of the traits that platforming characters have. Well defined graphics, awesome physics, a hitbox tied to a health pool, and it spontaneously explodes when you get to zero health. Perfect, done, ship it.

Something's wrong. I can feel it all the way deep into the back of my head. It's design sense - that feeling that you get when there's a perfect walkway and someone just happened to 'misplace' a brick because "only god is perfect". Some people call this OCD, but the feeling you're getting is cringe and out-of-order, not obsession.

The part that's wrong is obvious: A stick can't be a human no matter what you do. Unlike most video game characters this human violates the most basic principle of humans. Even if it walks like a human, speaks flawless English, and has an internal simulation that can spray blood everywhere, it still looks like a stick.

Instead of a random inanimate object that could be anything, let's make something real. How about my own avatar?

This human is highly stylized. it has eyes, legs, hands, and wears

clothes. It's not quite what we would imagine as a human, but that's not

the goal here. We're trying to build something close enough to a human

that it can't be confused with the stick.

The avatar is drawn

like this because it's part of an animation framework that lets each

piece be rotated, stretched, and manipulated independently. I did this

for stylistic reasons to begin with, but the idea lends itself towards

the cornerstone of this design.

Invariant 1: Humans can be divided into zones called Body Parts

Let's set up a few basic rules on top of this:

- Humans have six zones: left leg, right leg, left arm, right arm, head, torso

- Each part has its own pool of hit points

- The human is killed or otherwise incapacitated when their torso runs out of hit points.

This

gives us a lot of fine-grained control over a standard health pool. A

standard video game hero will run around smacking everything until

everything explodes into a puff of smoke, or they do the same. With this

setup, we can damage just the legs or arms.

An absolutely

hilarious thing that happens in a lot of video games is that you can run

out a character's hit points by throwing tiny pebbles at their big toe

over and over until they collapse. This chip damage is supposed to build

up over time and break the character's body. Any fighting game worth

its salt will give the character a block that reduces knockback, but may

still incur chip damage.

If

our character were to block continuously with a shield, then the damage

they would incur would be absorbed into their arm. Chip damage that

would normally wipe out the character instead breaks their arm.

Any

game that has equipment either picks an arm for a shield, or has the

hilarious effect of equipping two shields for no good reason. No game

that I have seen would ever have a two-handed shield. Here though? We

could hold the shield in both hands and have twice as much health to go

through before our critical torso is exposed.

Locational damage

in most games boils down to a critical hit system. Shooting someone in

the head grants double damage or shooting them in an exposed arm

bypasses any armor stats. Damage that hits a zone tied to behavior takes

that idea and turns it into a risk-assessment problem. For example:

"Knee-high acid is dangerous because it burns my character's legs until

they can't run anymore. I need to carry a grappling hook in case I have

to get out of the acid or my heart will get hurt."

Bats swoop

down on your head, trying to knock you unconscious. Loss of control,

lying prone, and having your torso exposed is a massive problem. It

means almost certain death. A savvy player will put extra protection on

their head, and a skilled player will use the character's blocking

ability to hit their arms instead of the head.

Enemies that

constantly target your legs from both sides are dangerous because you

can limp around on one leg, but two broken legs mean you're not going

anywhere. Backstabbing enemies are nasty not because they do extra

damage, but because they bypass your guard and go directly for the

heart.

The main advantage this gives the design is a sort of

gradient between one hit point and zero hit points. A character with a

broken arm will be unable to fight, but a character with a broken skull

may as well be dead if they're adventuring by themselves.

"Congratulations! Your Stick has evolved into Stick Figure!"

We've moved from a stick to a stickman. Let's put some flesh on those bones.

Magic systems are ubiquitous throughout gaming. The systems are usually simple: cast your fancy magic attacks from a pool of blue mana until you're depleted. Some games will throw in an extra stat like stamina or technique points, and a few will let you use hit points directly.

The mDiyo character wants to cast magic from 'life essence'. Most media is nebulous about this. Is it your spirit? Lifespan? Are you overweight most of the time because the best spells require your fat reserves?

Invariant 2: Each body part has four fantastic resource pools.

Some of our more fantastic spellcasters will realize that these pools represent the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Others will think they're talking about the fundamental essences of breath, spark, form, and life. mDiyo sees these and doesn't care; he want to cast magic from his life essence, his body, or wherever the heck it comes from.

Let's break down what each of these resource pools actually do.

Red is meat. These are the physical characteristics associated with a body part, or the amount of damage that it can take. Meat is directly tied to your health pool and having red energy is what causes their hit points to regenerate. Maximum red energy is the same as maximum health points, so more is always better.

Yellow is the stand-in resource for a hunger system. Most games merely have a meter that depletes over time, but Mabinogi takes this a step further and gives a lot of physical attacks a stamina requirement. Getting hungry makes the maximum amount of stamina you have deplete over time, and eating food will regain both some of the stamina resource and its maximum. Stamina regenerates slowly, and can be helped along by resting. Sleeping should set it to maximum - as long as you eat, of course.

Blue is breath, and its physical counterpart is oxygen. In any breathable space this should regenerate fairly quickly. Using blue energy as a resource for casting spells should allow for a lot of low-power, repeatable spells. Think something like an energy shot from an arm cannon or an aura that requires breathing techniques to function.

Green is the stand-in resource for what most games call 'mana'. Its physical counterpart should be hormones like adrenaline, or less tangible ideas such as prana, chi, midichlorians, or magicules. It can also be a measure of how awake the player is; running out of spirit means you get tired, grumpy, and stressed.

We can even compare green to chakras. Let's call it a physical manifestation of a divine energy unit and can use that to manifest the most fantastic ideas. Enhanced speed, superhuman punches, casting fireballs, or using Pokemon attacks are derived from this resource.

Most games have mana as blue. Most games also have their oxygen meter as blue or white. Almost no game has the two mechanics working together, and I would be very surprised if any of them would try to combine "cast magic from oxygen" and "I am hungry".

That just leaves one question: Why separate these resources into separate body parts? We don't have to, but having them does open up the design space for some interesting interactions.

Let's say that mDiyo wants to take a trip underwater. His lungs are stored in the chest, so normally he'd be able to spend about a minute underwater. Recently he visited a witch that taught him a special technique called 'deep breathing' to pull more breath out of his body and into his lungs. This technique can be performed as many time as he has body parts, so when the time expires he performs the technique and moves blue resource from his head into his lungs. Now he can spend two minutes underwater. Or six. Depends on how many times it's used.

"Congratulations! Your Stick Figure has evolved into Meat Golem!"

My design sense is still tingling. The mDiyo character may have some physical aspects that represent a body, but it's still lacking something... this version of the character isn't much better than an automaton or a meat golem. We need one more layer to make this design truly shine.

Invariant 3: Each body part has a set of attributes that can be manipulated via growth or status effects

This is the point where we start losing people. You can only keep so much information in your head at a time, and most people don't think on more than one level at once, so for the sake of keeping things manageable this needs to be consistent all the way through the design. The computer can keep track of everything; players will keep track of the effects, and maybe some of the numbers if they're into the metagame.

For consistency's sake, we'll give every body part exactly the same set of attributes. Let's also both arms into one class, so we don't need to worry too much about a missing left hand in our calculations. The same applies to legs. Let's also say that legs generally affect how a character moves, arms affect how a character interacts, head affects everything active that is neither of those, and the torso, heart, or body affects concepts that are innate to a character.

Each invariant has a set of rules built on top of it. Here's mine:

Strength (Red)

- Head: Intelligence

- Arms: Dexterity

- Legs: Jump Height

- Body: Carry Weight

Speed (Yellow)

- Head: Time Awareness

- Arms: Attack Rate

- Legs: Run Speed

- Body: Resource pool regeneration

Affinity (Blue)

- Head: Spellcasting

- Hand: Tools

- Legs: Movement Adaptations, Vehicles

- Body: Armor

Potential (Green)

- Head: Social Interaction, Fate

- Hands: Mysticality, Luck

- Legs: Athletics, Dancing

- Body: Physical Enhancement, Chi

One of the goals in this design is to try and take familiar game concepts, and re-mix them in a way that creates an extensible system to layer on other things. The design should be flexible enough that we can drop it in any game and robust enough that it stands up to the harshest scrutiny and the most obtuse system imaginable. Anything that can stand up to the utter design mess that is all of gaming will have an usual layout full of familiar ideas that end up in odd places. My particular focus is on some sort of RPG-esque metroidvania, so it runs the full gamut of ideas.

Each one of the pools has a particular concept tied to it. Most people wouldn't think about mixing intelligence with carry weight, and good luck trying to define what mysticality is. Let's go through each of these in turn before we try manipulating them.

Strength: A measure of the body's ability to push things around or otherwise manipulate the world around you. Raw strength itself can be measured as a stat. In specific body parts, it's a measure of how much force can be put into a task. High dexterity measures the speed and precision of handiwork, and is often associated with archery. A person with high intelligence will be able to connect patterns and recall information to solve a problem a lot easier than someone with low intelligence. The others are self-explanatory.

Speed: A measure of the body's ability to do things quickly. Some games will separate how fast a player can move and how fast they can attack; we can put these into the legs and hands respectively. The body itself has natural processes going on all the time, and generally tries to replenish its pools of fantastic resources as fast as it can. Anything that would affect regeneration should target the body's speed stat directly.

The odd one here is time awareness. How does that fit into speed? Well, if you've played a game where time manipulation is a mechanic at all, then I would say that someone is manipulating the person's head to move faster than the surrounding area. This carries over into all aspects, moving the player 'faster' while everything around them slows down, or even stops.

Affinity: A measure of the character's ability to understand something. This can happen through training, natural gifts, or experience. Anyone wandering around and leveling up is increasing their affinity stat, and all of the associated increases boost how well their natural strength works with tools or their natural intelligence works with spellcasting.

Potential: A measure of the character's limits in a category, both ceiling and floor. These are softer skills and more nebulous ideas. They may have varied effects that have little bearing on how the character actually does things, like luck changing the world around them or being able to manipulate fate directly.

The only way for a character to go beyond their limits is to increase their potential. A character with no limits has effectively unlimited potential.

Attributes are all well and good for calculating statistics, but we can do one better. Let's manipulate them. I cast Haste!

This is the fun part. Status effects need to target a body part to have any effect. Casting haste on a player's legs will let them run faster, while targeting their hands will have them stabbing things at lightning speeds. Targeting the body will accellerate natural processes, making the player regenerate health quicker at the expense of getting hungry faster. Hasting their head will increase their perception of time, slowing everything down around them.

A character on a long excursion may want to slow down their body processes. A monk of sufficient training may slow down their body to a stunning degree and have increased their regeneration to get back to 'normal'. Putting a character in stasis can cause all of their

The design broadens the Haste spell into a single idea. We target a resource and a body part, then decide whether we want to increase or decrease it. Give it a name, spread it around a bit, and we have some basic status effects.

Boost/Break: Targets strength

Haste/Slow: Targets speed

Enhance/Erode: Targets affinity

Shine/Dull: Targets potential

Status effects in other games tend to have the same problem as one hitpoint explosions do. The character is affected for a certain amount of time, something nasty happens, and it's at full potency the entire time you're afflicted. This is a relic of turn-based RPGs where everything is bunch of numbers on a spreadsheet with pretty animations. These ideas transfer poorly into games like platformers, with the exception of damage-over-time mechanics.

If we can target specific body parts, and body parts are associated with behaviors, then our effects can affect the behaviors instead of the stats. Doing something in real time has a very different effect from a turn-based game, so we need to be careful with this. The overall goal is still to make a human, after all.

Let's throw mDiyo off a cliff. BWAHAHAHAHAHA, er, this is bad. We could have his legs take a lot of damage for doing something like that, and if he falls far enough that's appropriate. If he falls three meters there's a good chance he'll be bruised a bit, the jolt will send shockwaves through his body, and he'll have to walk off the effects... but walk off he will. Instead of doing a bunch of damage to him, let's paralyze him for a few seconds instead.

Paralysis:

Stun (Can't move at all) -> Addle (Confused movements)

-> Slow (50% move speed) -> Recovery (75% move speed) -> Not

Afflicted

This is a layered status effect. Each one of them has a

timer and an expiration. The most potent level stops the entire character from working,

effectively leaving your character completely vulnerable to whatever

comes along. Falling off of a cliff does have its downsides, after all.

The

second layer is movements that make no sense. If mDiyo fell on his

butt, then he can probably get up during this time period, but good luck

doing much else with your legs. Attacking or using your noggin' should

be fine though.

The third and fourth layers are movement speed

reductions. These are the points where you 'walk it off'. Each of these

effects can take progressively more time. Stun might only last a second,

addle a couple more, but the slow and recovery could be an agonizing 5

seconds and 10 seconds overall time.

This whole setup is a

punishment to the player for not being good enough at covering their

mistakes. It's visceral: You can feel deep in your guts that you've made

a mistake by jumping off a cliff. The landing was botched, recovery was

poor, there was no double jump, and now you get to suffer the

consequences. It's also not so punishing that you could spontaneously

explode into meaty chunks. Worst case scenario: your character fell so

far that both of their legs are broken and now you get to sit there and

regenerate, drink a potion, or the game designer was particularly evil

and put spiders at the bottom of a ravine.

"Congratulations! Your Meat Golem has evolved into Fantastic Human!"

This system should encourage players to experiment with the character while still bringing the consequences of being a human into the mix. It's a bit hard to keep track of everything, but if we keep things consistent then players can pick it up easily enough. Most importantly, this design should go a long way towards making a character feel like they're more than a stick.

Combining all of the rules together, we have this set of rules:

- Humans have six zones known as body parts: left leg, right leg, left arm, right arm, head, torso.

- Each part has its own resource pool with a physical aspect and a resource counterpart. These pools are hit points (regeneration), oxygen (breath), hunger (stamina), and vital spirit (mana).

- Each part is tied to a set of behaviors that define a human. Legs for running, arms for attacking, head for seeing and interaction, body for passive effects

- Behaviors are measured with the attributes strength, speed, affinity, and potential. Changes to these behaviors are called Status Effects

- Each body part keeps track of its own status and can be manipulated independently

- The human is killed or otherwise incapacitated when their torso runs out of hit points.

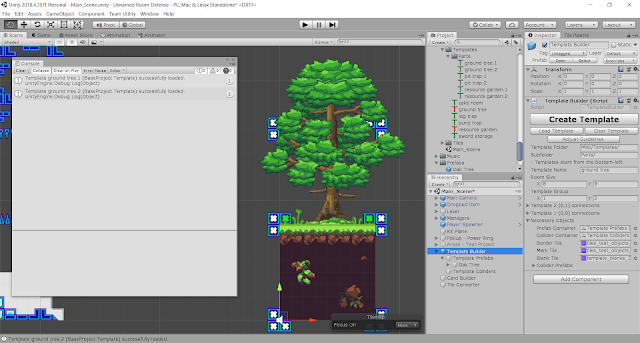

Whenever you have an idea like this, you need to have an entire game built up around it. As of right now I have very little. Writing this post has brought a lot of the ideas I've been thinking about together into one place and now I need to get it into this:

An idea is only the start of something. Like

Sivers says,

ideas are just a multiplier on execution. You need multiple ideas all

working on concert to get things rolling, and getting multiple layers of

ideas to work in concert is something else entirely. It's a good thing I

have very little to do or I would despair at the difficulty of this

task.

If there's one thing I am good at, it's layered design. Now I just need to get this to work.